How to Get Strong (A Complete Step-by-Step Guide)

May the force be with you

🎁 I’m giving away free access to my Principles of Strength and Conditioning course through Sunday. To get access » click here (your 100% discount is automatically applied)

📚 This is the first chapter of my book. You can find the full table of contents and other chapters for reference here.

Do you want to be strong or weak?

If I randomly polled 1000 people, I’m guessing all 1000 would say they want to be strong.1

That’s because strength is central to being a robust, antifragile, lifeproof human.

If you are weak, you are very literally fragile.

Strength then, like the other 5 core attributes, represents a difference in need not kind.

All humans must be strong, but how strong you want to be will differ depending on your specific needs and goals.

Let me give you an example. I believe ALL humans should be able to deadlift at least their body weight. Period. That’s the bare minimum requirement to play the game of life.

Now, you are welcome to push that number up as high as you want depending on your specific needs and goals. Like a former client of mine, Ben Eisenmenger, who made 740 lbs look like child’s play.

That obviously creates quite a range…

On one end, we have deadlifting your body weight, and on the other, we have throwing around 740 lbs…

The question then isn’t whether should you be strong, but rather, where do you want to fall on the spectrum of strength?

While I can’t answer that question for you, I can give you the tools you need to own your strength and build it to whatever level you desire…

And that’s what this chapter is all about - how to get strong 💪

Here’s a small taste of what you’ll discover if you read this chapter:

A clear understanding of what strength is (and more importantly what it isn’t).

Why nearly all popular fitness programs (like F45) are not making you strong (despite their marketing efforts).

Why weight on the bar is the king of strength gains.

How to use autoregulation to blast through plateaus and be stronger than ever before.

The best exercises for building strength.

The exact sets, reps, and rest times to use to explode your strength.

A done-for-you 12-week strength block that’s created multiple 100lbs PRs

Our strength standards so you can see where you stack up and have goals to shoot for.

Strength Case Study - What’s Truly Possible

Before we get started, I want you to know what’s truly possible for your strength if you follow the strategies and tactics I lay out in this chapter.

I’ve found having a standard to hold yourself to and seeing that others before you have done it, goes a LONG way in helping you succeed…

Mickey is a husband, father, and CEO who, like many men, sacrificed his strength, physique, and health for years while he focused on his family and business.

One day though, he said enough is enough and decided to re-prioritize his own fitness and training.

Here’s what happened in just 6 months:

If you’re not too hot on math, that’s a cumulative 300 lbs PR in 6 months…

I’m curious, do you want results like that??

If so, keep reading 💪

Strength - A Real World Definition

Strength is the ability to generate force, which we define mathematically as force = mass x acceleration.

Of those 2 variables, mass is king, and in the real world, we measure that by how much weight you can lift.2

Thus, our simplified definition of strength is:

Strength = how much weight you can lift.3

This is expressed nicely in a sport like powerlifting. If person A can lift 200 lbs and person B can lift 300 lbs, person B is stronger. Period.

I can already hear people bitching about body weight, so let’s stop that right now with a real-life example.

If a tree was blocking the road, and it needed to be lifted out of the way, nature doesn’t give a damn how much you weigh. Some amount of force will need to be generated to lift the tree out of the way, regardless of your body weight.

If you weigh 150 lbs and can’t lift the tree, the road remains blocked.

If someone else who weighs 300 lbs can lift the tree, the road gets cleared.

The person who could generate enough force to lift the tree is stronger. Sorry, but that’s the cold hard truth of nature.4

What Is Strength - Necessary Background Science

I believe some level of background science is required to best understand what strength is AND how to train it.

If you think of yourself like a video game character, strength is the attribute bar you are looking to increase.

But what are the component parts of strength?

In other words, if you wanted to write an equation for strength, what variables would you care about?

For example, if A = B + C + D, then you know you can increase A by increasing either B, C, or D…

That’s what we will do in this section - clearly define strength and write out a strength equation so you know exactly what variables you are looking to improve.

Central and Peripheral Factors

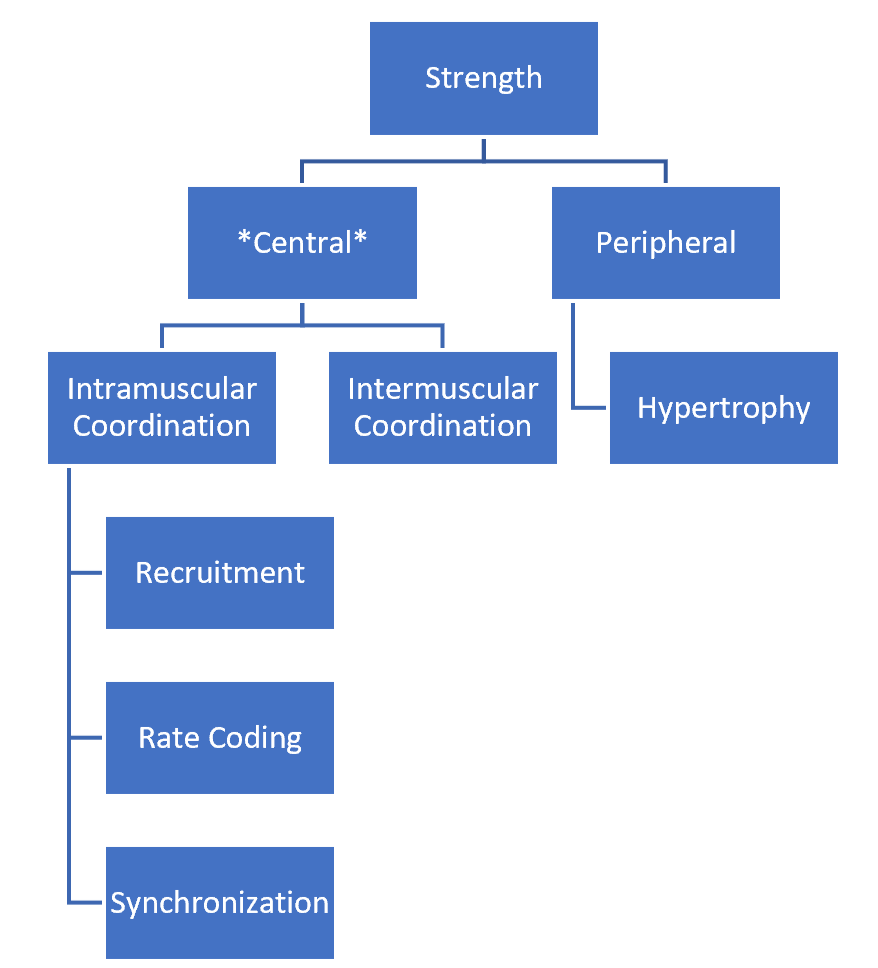

You can break strength down into its component parts as follows:

As you can see, strength is comprised of both central and peripheral factors.

Central refers to your central nervous system, while peripheral refers to your muscle mass and dimensions (i.e., hypertrophy).

If you think about this on a spectrum, the central adaptation plays a larger role as reps decrease while the peripheral adaptation plays a larger role as reps increase.

Since I’m devoting an entire chapter to hypertrophy later on, this chapter will focus on the central adaptation and left side of this spectrum.

It All Starts With A Muscle Contraction

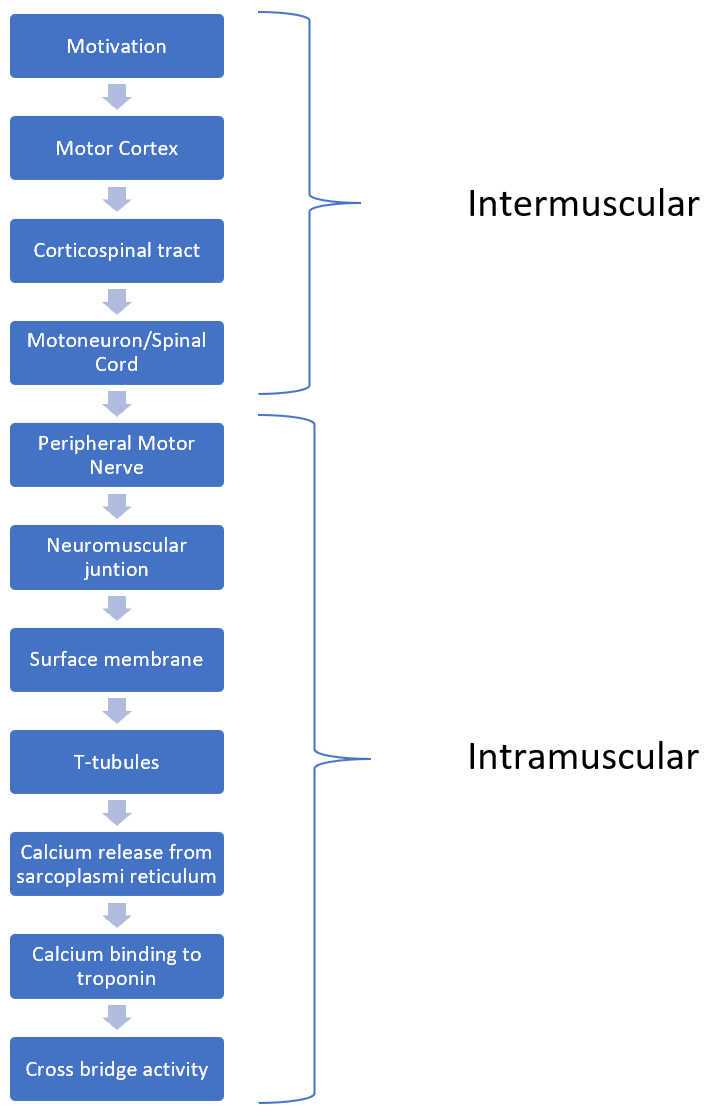

This gets a little into the weeds, but hang with me. I believe to truly grasp the central factor of strength you need to have a working understanding of a muscle contraction. In particular, pay attention to the number of steps required for a muscle to contract.

A motor unit consists of a motor neuron in the spinal cord and the muscle fibers it innervates. In order to contract a muscle and generate force, an electrical signal originates in your brain and travels down the spinal cord to the appropriate motor neuron. The signal then travels down the axon and to the neuromuscular junction, where acetylcholine (ACH) is released and binds to receptors in the motor endplate. This binding causes special channels to open in the motor end plate, allowing sodium to rush into the muscle cell.

The influx of sodium (a positively charged ion) causes the muscle cell to depolarize, which triggers an action potential that propagates along the sarcolemma and down the T tubules. As the action potential travels down the t-tubules, it hits a protein called the DHP receptor causing it to change shape and open a second protein in the sarcoplasmic reticulum membrane called a Ryanodine receptor. The Ryanodine receptor is the gatekeeper to calcium release, and much like Gandalf, it usually says “you shall not pass.” This all changes when the action potential arrives, and the opening of the Ryanodine receptor allows calcium to pour into the cytosol.

Calcium then finds and binds to troponin, which opens up the myosin binding sites on actin so cross-bridge cycling (muscle fiber contraction) can occur.

If we zoom out and look at this cascade from the top down, here’s what you’ll see:

You may be wondering why I took you into the weeds right off the bat, but the reason is simple: I want you to see all that must happen for a single muscle to contract.

Look at all the moving parts and how everything must coordinate from the initial motivation to the final muscle contraction.

If you want to be strong (generate large amounts of force and lift heavy weights) then every step in the above cascade must be fine-tuned. Everything from the conduction velocity of the electrical signal, to sodium and calcium handling, to how many muscle fibers a neuron innervates. It all matters. And every time you train strength, you are training this cascade.

Intramuscular Coordination - Coordination Within a Muscle

We care about the nitty-gritty of the motor unit because that’s where the intramuscular adaptations take place, which include:

Recruitment

Rate coding

Synchronization

I’ve found the best way to think of these is to consider rowing a boat. If you wanted to form a team and row as fast as you can, how would you do it?

Well, option 1 is to get more people in the boat rowing. That’s recruitment. You are recruiting more muscle fibers to the task at hand and can thus generate more force.

Option 2 is to increase the stroke rate of the people in the boat. If you can hit 20 strokes per minute as opposed to 10 strokes per minute, you will go faster. This is rate coding. By increasing the discharge frequency of motor neurons (otherwise termed firing rate), you can get a muscle to generate more force.

Option 3 is to have everyone in the boat rowing in a coordinated manner. If you have 10 people all rowing at the same exact cadence, then you will do far better than a team rowing out of cadence. This is synchronization and speaks to your ability to coordinate contractions optimally.

To generate as much force as possible, you need all three on board.

Intermuscular Coordination - Coordination Across Muscle Groups

The primary driver of strength is the central nervous system’s ability to coordinate action across numerous muscle groups.

In case you are confused, intramuscular refers to actions within a single muscle group, while intermuscular refers to the complex coordination of numerous muscle groups. Intermuscular is concerned with the entire movement pattern, rather than the strength of single muscles or the movement of single joints.

Think about the difference between a dumbbell curl and a max-effort back squat. Intermuscular coordination plays a HUGE role in the squat and a minimal role in the curl. In the squat, you are having to coordinate across nearly every muscle to perform the task at hand.

Here’s a simple example.

Imagine you are at a country fair with a high striker…

It’s the game where you take a hammer, hit a pad, and see how far you can drive a puck up a column.

Let’s say it’s just you hitting the pad. How complicated is that? You tell yourself to slam the hammer down, and you do it.

What if I now put you on a team of 8 individuals, and the goal is for all of you to slam the hammer down at once to generate as much force as possible? More complicated? You bet. Just because you shout “slam” doesn’t mean your 7 teammates will do so in unison. It will take time and practice to get everyone working together to generate a coordinated, optimal outcome.

This is exactly how I want you to think of intermuscular coordination - your brain shouts a signal, but it takes time and practice for the signal to reach the different parties and get them to fire together in unison.

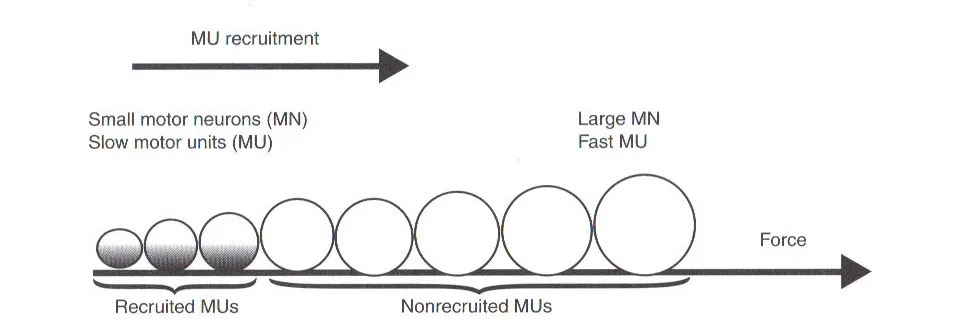

The Size Principle

While the size principle technically falls under the umbrella of recruitment, I think it deserves its own section to help drive home why weight on the bar is king when it comes to developing strength.

Motor neurons fall on a spectrum from small to large. The smaller motor neurons tend to innervate slower twitch fibers with lower force-generating potential, while larger motor neurons tend to innervate faster twitch fibers with higher force-generating potential.

During a voluntary contraction, the order of motor neuron recruitment is dictated by the size of the motor neuron - smaller motor neurons are recruited first followed by larger motor neurons as needed.

If the force requirement is low (i.e. lifting lightweight) then only smaller motor neurons are recruited. If the force requirement is high (i.e. lifting heavy weight), then you recruit the larger motor neurons.

In order to be strong, you must recruit the largest motor units, and you improve your ability to do so by lifting heavy weights and generating large amounts of force5

📝 Science Summary

In summary, strength is about teaching your central nervous system to recruit the most muscle, at the fastest rates in the most coordinated manner.

As an equation, it’d look like this:

Now that you know what variables you are looking to train, let’s break down how to do it in the real world.

Like most things - the underlying science gets rather complex but WHAT you need to do is actually very simple.

⭐️ Quick Aside - What Gets Challenged Adapts

If you take nothing else away from this post, please remember this universal rule - what get’s challenged adapts.

If you want to get stronger, then you must CHALLENGE your physiology’s ability to generate large amounts of force…

And you do that by lifting heavy weights.

If the external challenge isn’t there, your body has no reason to change or adapt.

That’s why F45, bootcamps, and any other training methodology that involves moving continuously through a high-rep circuit, are not making you stronger.6

Strength Application - How to Get Strong in the Real World

🎁 If you’d like a free done for you 12-week strength block that’s created multiple 100lbs PRs » CLICK HERE.

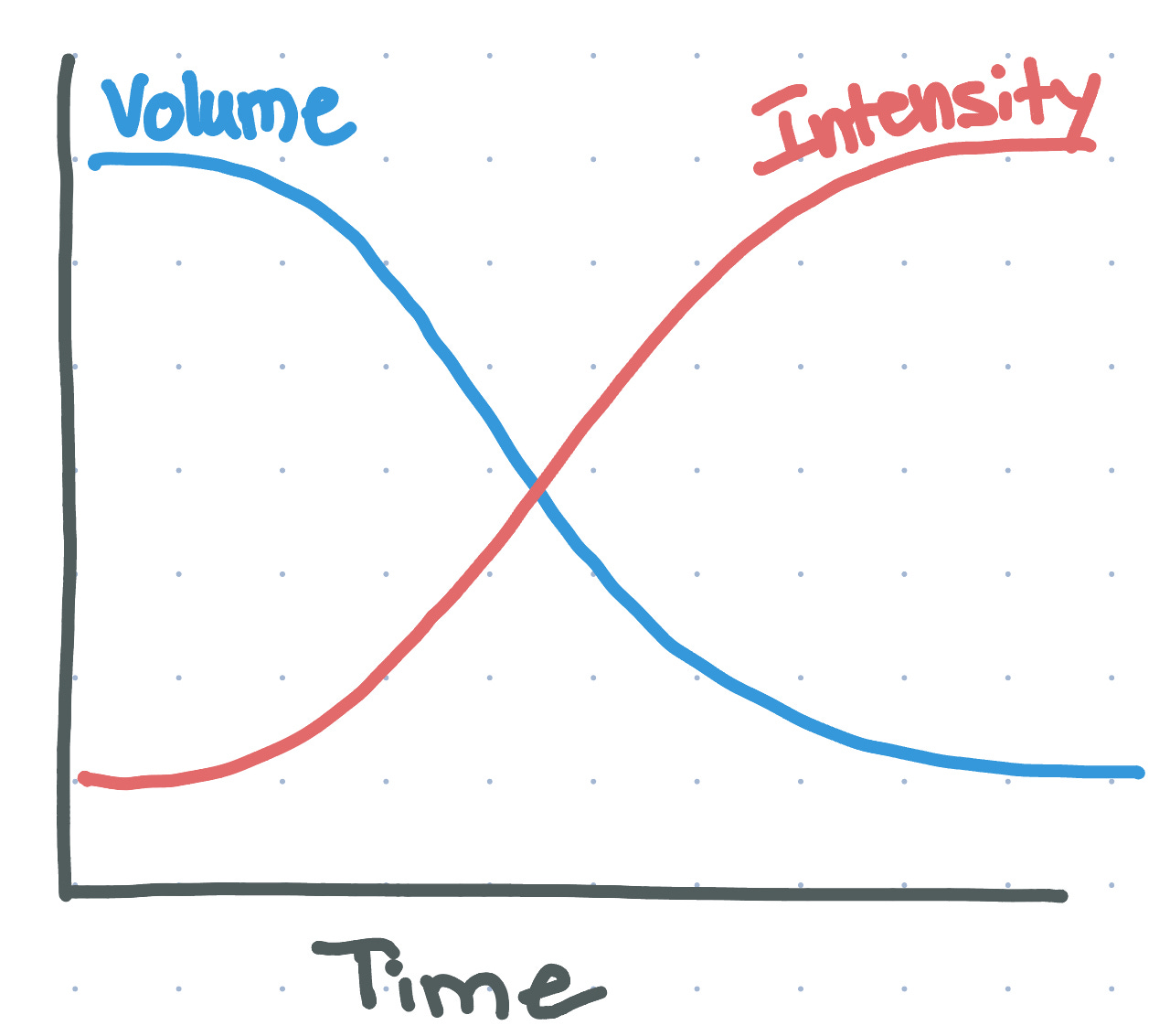

1️⃣ Intensity Accumulation

In order to build strength, you must focus on intensity accumulation. This means increasing intensity (weight on the bar) and decreasing training volume (total reps performed, or total weight lifted) over time.

It looks a bit like this:

While there are many strategies you can employ here, a great place to start is Prilepin’s chart.7

The basic idea, as mentioned above, is to move from high volume and low intensity to low volume and high intensity over the course of a training program. You can see this on the chart below by starting at the top and moving down (follow the blue arrow).

Note how volume starts high (total rep range of 18-30) and decreases over time (total rep range of 10), while intensity starts low (55-65%) and increases over time (90%+). This balancing act is to accommodate the increased stress placed on your central nervous system as intensity increases.

For example, a 2x2 at 90% places far greater stress on your central nervous system than a 3x10 at 60%. Your CNS can only handle so many reps at or above a particular percentage before it taps out, and you’re responsible for managing that.

Now, I can tell you from experience that your bread and butter percentage range lives between 65-85%. You want to train, accumulate and spend the vast majority of your time in that percentage range to build strength.

Then only touch 90%+ when it comes time to peak or enter a realization phase.

Ultimately, there are countless ways you can go about programming for strength, but regardless of how you do it, intensity accumulation will always be at its core.

2️⃣ Autoregulation

I am not a wizard and cannot predict the future, and neither can you. Despite my efforts as a coach to always write the best set and rep scheme, there are too many constantly changing variables to do so successfully. Plus, you have HUGE inter-individual differences with regard to how you respond to training - some do really well with higher volumes, while some will get crushed.

In other words, I don’t know what the “perfect” amount of work/stress is for you on any given day. Instead of guessing, I bake autoregulation into every training program I write. That way I guarantee each athlete I coach is working to where they need to be that day.

Here’s how it works…

Pick a load and rest time, and then have either sets or reps left as a question mark. Let’s walk through two examples:

In example 1, I have locked the reps, load, and rest time, but left the total number of sets up to the athlete. This means the athlete will do 5 reps at 70%, rest a strict 90 seconds, and then keep hitting sets until quality falls off.8

In example 2, I have locked the sets, load, and rest, but left the total number of reps up to the athlete.9 The athlete will hit as many reps as they can, rest 5 min, and do it 2 more times for a total of 3 sets.10

The entire goal with autoregulation is to meet the athlete where they are on that day and ensure they are working hard enough/applying enough stress to drive a significant adaptation.

Another popular autoregulation tactic, that I’ve had a lot of success with, is using an estimated daily max (also known as EDM). Here’s an easy example:

Work up to a max for the day of x reps leaving y reps in the tank. For example, work up to a 6-rep max leaving 3 reps in the tank.

You then remove 15% of the load from the bar and hit an additional 2-4 sets with a strict rest time of 2-3 minutes. For example, say you hit 315 lbs for your top set of 6, that means you’ll drop the weight to 268 lbs, and hit 2-4 sets of 6 reps with 2-3 minutes rest between sets.

Regardless of the autoregulation method you choose, I think you’ll be pleasantly surprised with the results it generates. Just remember to decrease volume and increase intensity over time.

3️⃣ Quality Over Quantity - Invert Your Sets and Reps

By this point, you should be comfortable with the idea that strength gains are largely about what’s happening in the central nervous system.

So, the buzzword you care about is quality. Much like when learning a skill, performing lots of sloppy reps will not help you improve.

The same goes for strength. Performing tons of fatigued, sloppy reps isn’t helping you. You need to care about the total number of HIGH-QUALITY REPS you are hitting so your central nervous system can learn the skill of strength.

That’s why I prefer to invert sets and reps when chasing strength. Instead of doing 5 sets of 10, I’d write 10 sets of 5. In both cases, you are hitting 50 total reps, but I’d bet everything I own you are hitting more quality reps with greater intent in the 10 sets of 5 scheme.11

4️⃣ Take Your Time

How long do you rest in between sets when your goal is to increase strength?

The typical answer is 2-5 minutes, but studies are starting to show that resting longer might be more beneficial for maximal force output.

In other words, don’t rush.

When you want to get strong, take your time between sets and make sure you recover.

5️⃣ Choose Exercises That Prioritize Load

Since strength is about lifting heavy weights, you need to choose exercises that allow you to actually lift heavy weights.

This may seem obvious, but I am constantly amazed by how many people violate this basic rule.

For example, you will not get strong doing zercher squats or kettlebell goblet squats because you are load capped.

Just like you will not get strong by doing lunges and curls together…

Or hopping up and down on a bosu bowl…

Or doing banded bodyweight squats…

Or doing never-ending high rep circuits…

And the list goes on.

The kings of strength development are big, bilateral exercises like squats, deadlifts, and presses.

If you want to get strong, avoid exercises where you are load capped.12

6️⃣ An Important Note on Velocity

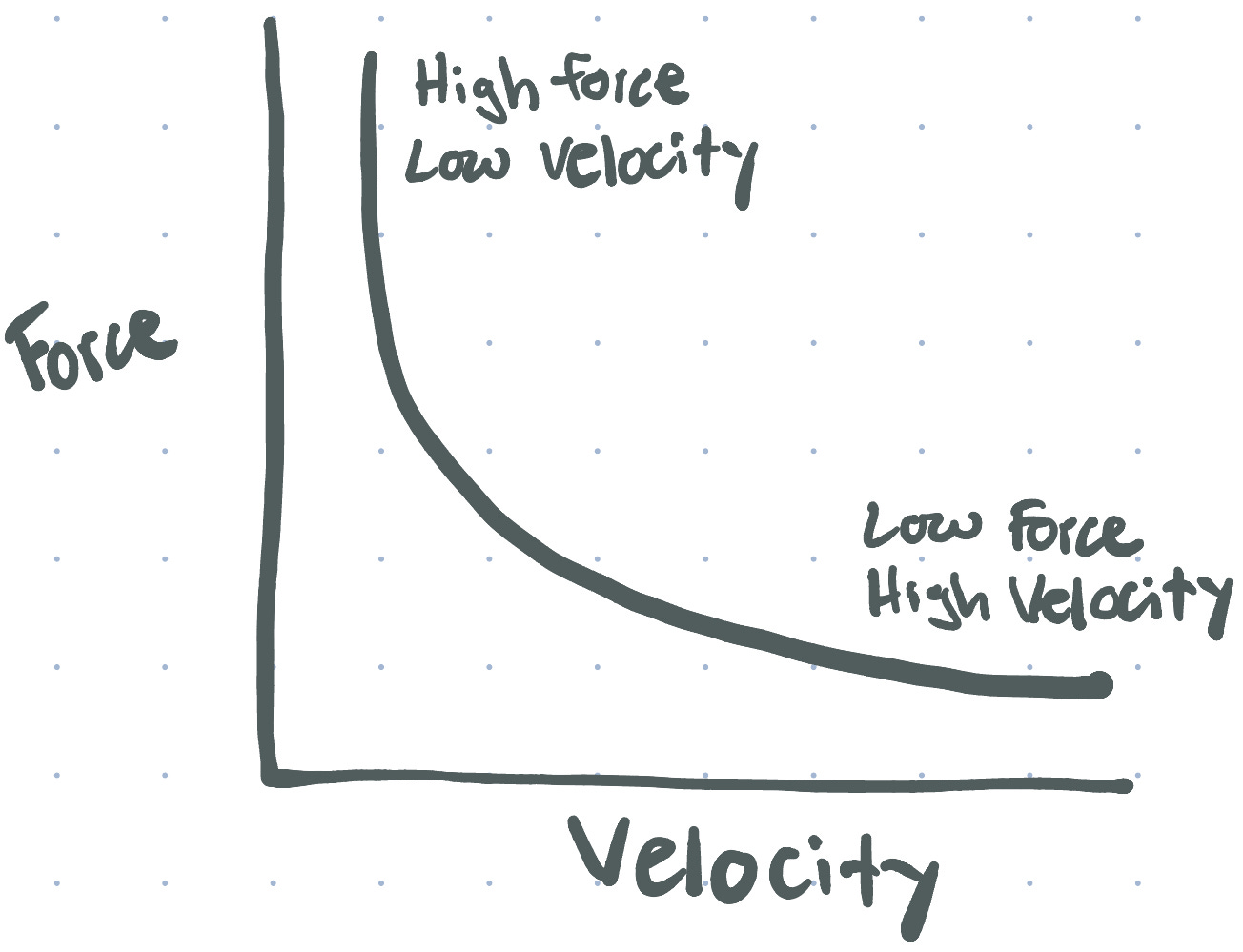

As load goes up, velocity goes down. Very simple. You can see this in a force-velocity curve:

Notice how strength (muscle force) increases as velocity decreases and vice versa. You can only generate so much force against a low load. In order to generate maximal force, and thus strength, you must rely on heavy loads that move slow.

That does not, however, change your intent. The only reasons bar velocity should decrease are because the load has increased, or you’ve become fatigued. It should never decrease because you don’t bring the appropriate intent to the table. Your goal must always be to attack the weight and move it as fast as possible.

There are two important points here:

Strength is not power. Strength is all about maximal force, and maximal force means velocity has decreased. Last time I checked, there isn’t a shot clock on your max deadlift. As long as you stand it up, it counts.

Improving strength past a certain point may make an athlete worse because he or she will become slower.

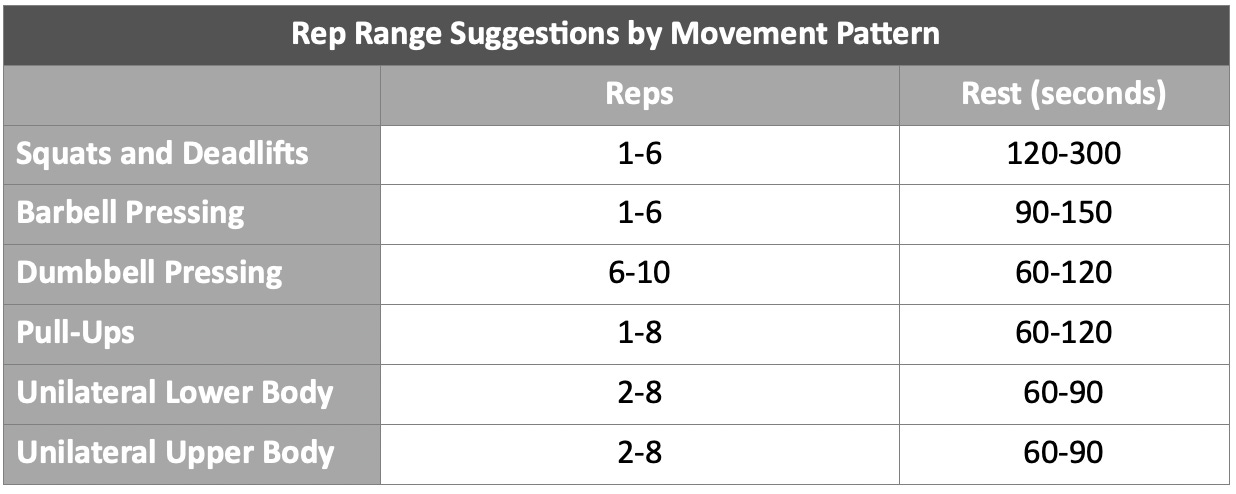

Strength Training Guidelines

Here’s a very generic summary of everything laid out in this chapter. The bell curve is used to depict where you should spend the majority of your time.

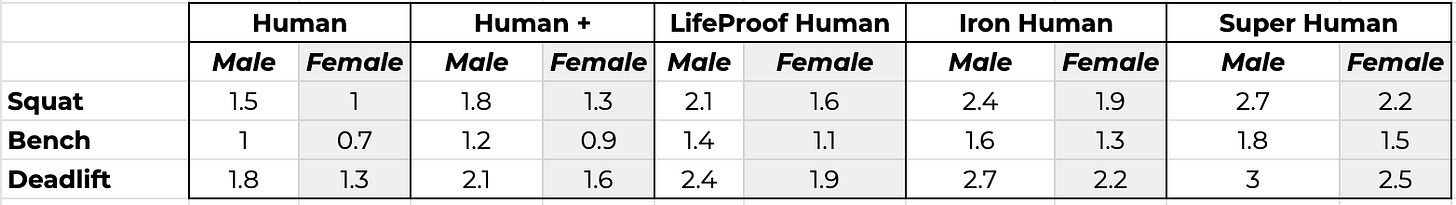

Strength Standards

Here’s how our athlete classification system works (note: we have very high standards and you should too):

Level 1 = Human

Our baseline expectations for any functioning human

Level 2 = Human+

You laugh at mere mortals

Level 3 = Lifeproof Human

You are beginning to enter a league of your own

Level 4 = Iron Human

You are a savage

Level 5 = Super Human

You have evolved into a new species

Here are the numbers specific to strength. They are shown as a multiple of body weight. To calculate your standard, take your body weight and multiply it by the number in each cell.

Here are 3 examples of different body weights to give you real numbers to relate to (you can find the body weight in the blue box in the image).

In Closing

Getting strong is not complicated, but it does require consistent hard work.

What I’ve laid out here may seem overly simplistic, but it’s been tested and proven on thousands of people over the past decade.

If you take the time to absorb what’s here and put in the work, I promise you can be stronger than you ever thought possible.

Also, if you found this useful, can you do me a favor and share it?

I’m not really big on asking for these types of things but I’m trying to help as many people as possible and I think it takes less than a minute. So, if you can do that it’d make me love you very long time, and since I’m giving it all away for free, it’s my only ask.

Much love.

James

P.S. Feel free to drop questions in the comments below 😉

My projects (if you’re interested…)

🦍 The silverback training project – this is an exclusive 16-week training and nutrition coaching program for men that want to look better, feel better and perform better than ever before.

🤑 The wealthy fit pro – this is an exclusive 6-week coaching program for fitness professionals that want to get more clients and make an extra $1000-5000 per month online.

🏋️ Principles of strength and conditioning course – this is where I show you how to empower your own performance by teaching you to write training programs that get record results in record time for your physique, health, and performance.

💨 The oxygen course – this is a course for those brave souls that want to dive into the weeds and learn graduate-level respiratory, cardiovascular, and muscular physiology without the graduate school price tag.

Especially if you could download strength matrix style without having to do the work.

Acceleration matters, but only to the point that it’s not 0.

There are many types of special strength, relative strength etc, but we are not going to worry about them. In the real world, strength comes down to weight lifted. Period. The rest are just semantics.

Obviously the person who weighs more has an advantage. As the saying goes “mass moves mass.”

This is why athletes engaged in strength and power training show increased motor unit activation compared to non-trained individuals. The athlete has learned over time how recruit more muscle to the task at hand.

UNLESS you’re incredibly detrained.

This was developed by Soviet national coach AS Prilepin back in the 70’s after reviewing the training journals of thousands of Olympic weightlifting athletes. Please note that it’s a great place to start conceptually, but it isn’t the bible. The percentage ranges, reps per set, optimal and total rep range are merely guidelines to get you in the ballpark. You’ll want to use your own experience and data collection to fine tune.

With this type of protocol, I’ve found it’s helpful to cap the set total because athletes with a slower twitch profile can go all day long. For example, I’d say your sets are capped at 8, if you reach the 8th set, take it for as many reps as you can and move on.

This is an especially brutal but highly effective protocol in the 80% range.

When performing this protocol, I usually limit the amount of time between reps to 2 Mississippi, so the athlete doesn’t hangout all day between reps.

2 notes. First, this is where example 1 in the autoregulation section is really powerful. Second, if you invert sets and reps, be sure to adjust your rest time accordingly.

This is why machines like a hack squat or pendulum squat make A LOT of sense for most people. It removes the technical limiter and makes it all about load. If you are uncomfortable chasing load with a bar, then find machines to use instead.