How to Build Muscle (A Complete Step-by-Step Guide)

"Everybody wants to be a bodybuilder, but don't nobody wanna lift no heavy ass weight." - Ronnie Coleman

This is chapter 2 of my book. For other chapters and a full table of contents - go here.

Last week I was hanging out with some friends and, like all good barbecues, we started talking about building muscle…

While we jammed on this topic around the grill (to the chagrin of our girlfriends, fiances, and wives) I realized that people need an easier way to think about hypertrophy.

Yes, you can make it really complicated and get lost in the weeds of cellular mechanisms, but from a practical standpoint, is that really helpful? Does better understanding mTOR (which no one actually understands) help you build muscle?

I don’t think it does…

From a sets, reps, and protocol standpoint, we know what works but I find people are still lost and confused when it comes time to EXECUTE and put a plan into ACTION.

And that’s what really matters here → results.

But if you can’t see the forest through the trees, then you will get lost in the minutia and never put a concrete plan into action. You’ll keep spinning your wheels worrying about details that need to be left to scientists in the world of research…

So, how can you make hypertrophy and building muscle “simple”?1 What are the major variables you need to control in order to love what you see in the mirror?

I’ve written this chapter to unpack the 6 core variables you need to control to drive muscular hypertrophy. No more overthinking and overanalyzing your training. Just results. And it all comes down to this simple hypertrophy equation:

Hypertrophy = (volume accumulation) + (mechanical tension) + (metabolic stress) + (does it suck) + (lengthened and shortened) + (tempo)

Let’s do this 💪

Here’s a small taste of what you’ll discover if you read this chapter:

The difference between sarcoplasmic and myofibrillar hypertrophy (and if you should even care)

A done-for-you Muscle Building Sets and Reps Cheatsheet (to fast-track your results)

The #1 predictor of muscular hypertrophy (hint - it’s volume accumulation)

The exact sets, reps, and rest times to use to make your muscles bigger (this is all about manipulating metabolic stress and mechanical tension)

THE secret ingredient of hypertrophy training (without this you will never grow)

How to fully stimulated a muscle by training it in the lengthened and shortened position (without this you will leave gainz on the table)

Our hypertrophy standards so you can see where you stack up and have goals to shoot for.

Hypertrophy Case Study - What’s Truly Possible

As a former rower in college, Dr. Charlie can go all day but his job demands more of him because when things go wrong deep in the mountains, he’s your guy.

He’s the one showing up on the helicopter to save your life.

And that means having to ruck a massive pack potentially miles into the backcountry and then pick up, move, or lift a human and/or some other object.2

Unlike like most folks - his performance is truly life or death for the people that count on him…

Yet what was missing for Charlie was both strength and size. He hadn’t quite figured out how to add size and strength without sacrificing his endurance or ending up in pain.

Fast forward 1 year, and Charlie has put on 18 lbs, added 100 lbs to his squat and bench, got rid of some nagging pain, and remains as fit as he was when he rowed in college.

That’s what winning looks like, and today, I want to help you do the same.

Hypertrophy Background Science

First, some necessary vernacular. A muscle belly is a collection of fascicles. A fascicle is a collection of muscle fibers. A muscle fiber is a collection of myofibrils. And a myofibril is a collection of actin and myosin, also known as the contractile elements of muscle.

Obviously, there’s a lot more going on here. You have connective tissue, vasculature, nerves, muscle stem cells, and the sort, but this simple classification brings you up to speed on the muscle tissue-specific terms.

Hypertrophy comes in two forms:

Sarcoplasmic hypertrophy (sometimes referred to as non-functional)

Myofibrillar hypertrophy (sometimes referred to as functional)

In the graphic below, you can appreciate the difference.

Sarcoplasmic hypertrophy consists of the growth and expansion of non-contractile elements - think things like sarcoplasmic protein content (enzymes) and glycogen. Myofibrillar hypertrophy, on the other hand, is the enlargement of the muscle fiber as it gains more myofibrils, and, correspondingly, more actin and myosin filaments.

The overall effect remains the same, a larger muscle fiber, but the finer details, such as how to prioritize one over the other or how much each contributes to gains in strength, remain in question. I will let you peruse Google Scholar and PubMed if that’s something you want to learn more about.

For our intended purposes, what matters is this:

Having bigger muscles looks awesome

Larger muscles can generate more force3

Hypertrophy Application - How to Build Muscle in the Real World

🎁 If you’d like a done-for-you Muscle Building Sets and Reps Cheatsheet that’ll build lean muscle faster than you think is possible » CLICK HERE.

1️⃣ Volume Accumulation

If you remember back to the strength chapter, you’ll recall that building strength requires a focus on intensity accumulation.

Hypertrophy must also focus on accumulation, but it needs to focus on volume accumulation.

Here’s how you calculate it: sets x reps x load = volume

Volume accumulation is incredibly important because it’s the number one predictor of muscular hypertrophy and should increase over a given periodized training cycle.

Here’s a very basic example of what that may look like over the course of 4 weeks:

Week 1: 3 sets of 10 at 315 lbs = 9450 lbs

Week 2: 3 sets of 10 at 320 lbs = 9600 lbs

Week 3: 4 sets of 8 at 320 lbs = 10240 lbs

Week 4: 4 sets of 8 at 325 lbs = 10400 lbs

Notice how total training volume increases week over week.

This is the hallmark of a hypertrophy block - you accumulate volume over time as opposed to intensity (which occurs in strength blocks).

2️⃣ Mechanical Tension and Metabolic Stress

When choosing sets, reps and rest times, there are two key variables you need to control for hypertrophy:

Mechanical tension produced by force and stretch

Metabolic stress produced by metabolite accumulation

And here’s how to think about them:

To dial-up mechanical tension, you must increase the load, decrease the reps, and increase the rest time. For metabolic stress, you must decrease load, increase the reps, and decrease the rest time.

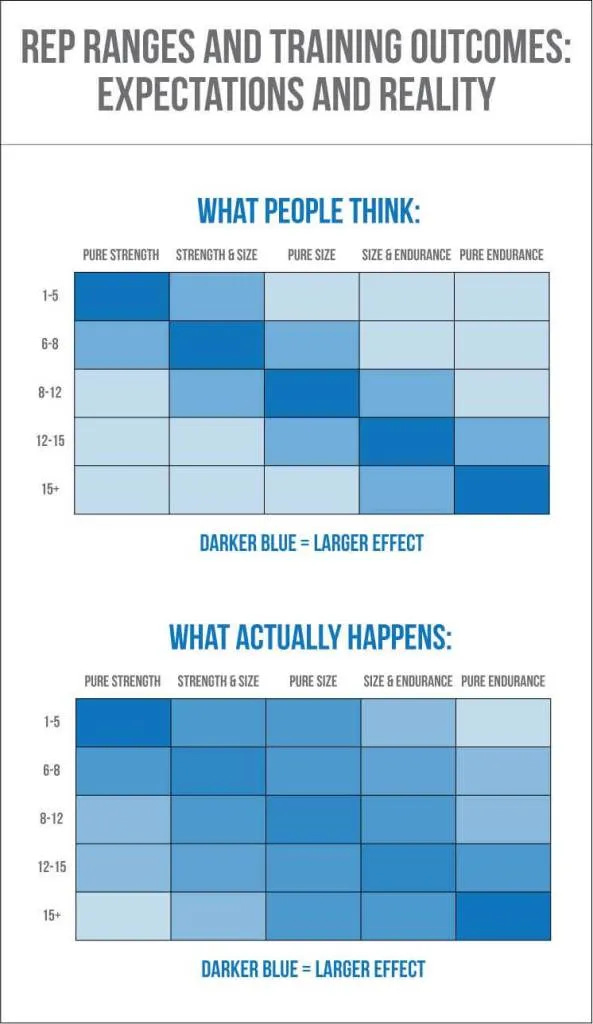

For reps, anything from 3-20 can do the trick. Let’s place those on a bell curve to help visualize it:

You obviously have a lot of room to play with, so what’s optimal?

Well…just look at the bell curve. What part of the curve has the most area under it? Because that’s there where you should spend most of your time. It’s not the 3 and definitely not the 20. They lie at the extremes. What lies in the middle is the sweet spot, and classically it’s thought to be 8-12 reps, but we can honestly say it’s more like 6-15

So, 6-15 reps are your bread and butter range, and you can extend off of that in either direction depending on if you want to dial up more metabolic stress or mechanical tension. As you do, be sure to respect what must happen to rest time and load as displayed previously in figure 2.

Let’s go ahead and fill those in to capture the whole picture:

Note that “optimal” will be impacted by the type of movement you are performing. For example, think about a squat vs. a dumbbell reverse fly. How effective will a “heavy” set of 5 be for a dumbbell reverse fly? The answer is it won’t. The exercise is inherently self-limiting because you don’t have a large range of loads to choose from.

Thus, it’s a safe bet to assume you will shift toward metabolic stress as the size and number of muscle(s) involved decreases.4

If you’re feeling a little lost, this is a good graphic to help summarize and visualize the rep story from the folks over at Stronger by Science:

3️⃣ Does It Suck?

Now that we’ve laid the foundation for metabolic stress, mechanical tension, rep ranges, load, and rest, let’s talk about the “secret sauce” of hypertrophy training: it has to suck.

Yep, you read that right. To drive hypertrophy, whatever you are doing must suck, but this should make plenty of sense from an evolutionary standpoint. Carrying around excessive muscle mass is inefficient, unnecessary, and expensive, so you need to go hard as hell to convince your body that it’s necessary.

It doesn’t matter if you are doing 3 reps or 20 reps, it has to suck. And we can quantify suck using your rating of perceived exertion (RPE).

Here’s a handy table for that:

The magic number you care about here is 7.5. You need to be at a 7.5 or above to drive hypertrophy.

You can manipulate reps, load, and rest as much you like, but if it never sucks (aka. reaches a 7.5 RPE), then you aren’t creating change at the muscle.

Similar to the strength story - this is why most popular fitness programs never build muscle. You run around out of breath doing glorified cardio for 45 minutes without ever crossing the suck threshold required to build muscle.5

4️⃣ Train Lengthened and Shortened Positions

A muscle, like a rubber hand, has both lengthened and shortened positions.

If you stretch the 2 ends of the rubber band farther away from each other, you have put it in a lengthened position.

If you bring the 2 ends of the rubber band closer together, you have put it in a shortened position.

The reason this matters is that a muscle will respond differently to being trained in the lengthened vs. the shortened position.

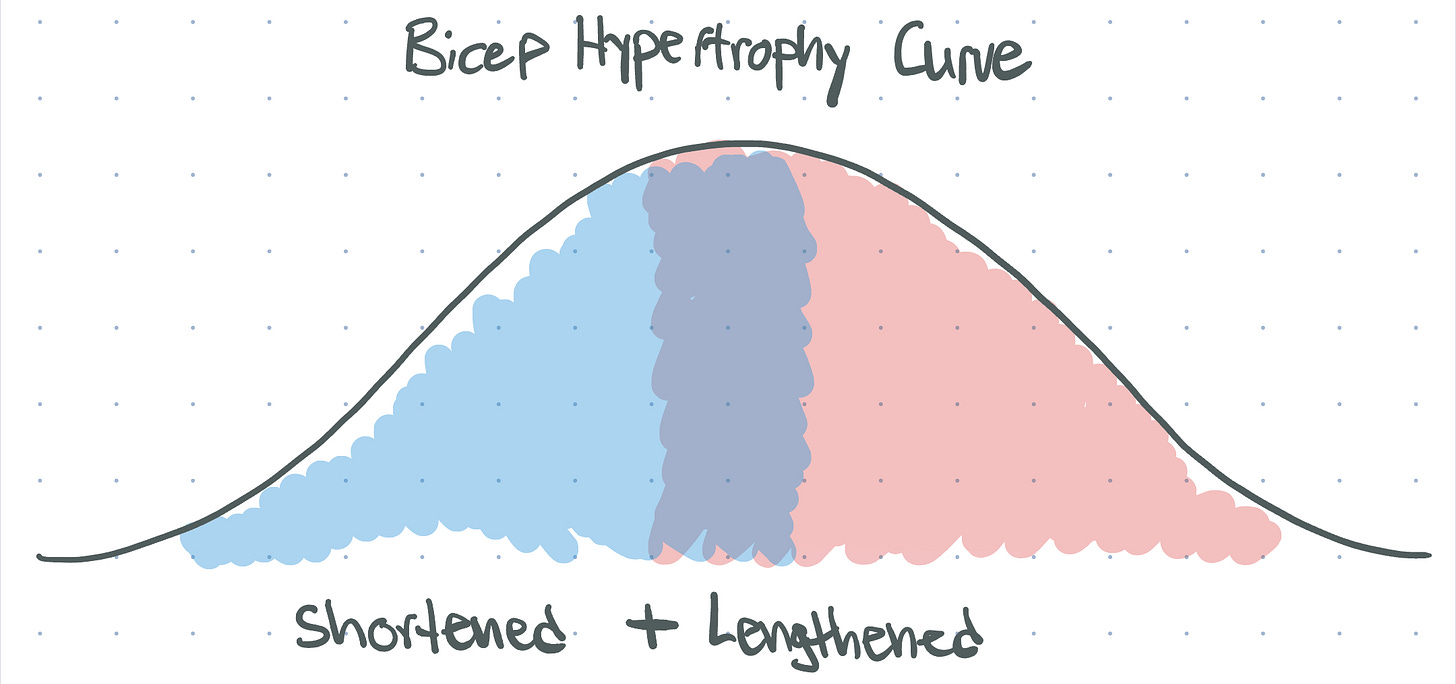

One is not better than the other. You just want to make sure you utilize both positions. Don’t do just lengthened and don’t do just shortened. Use both.

Here’s an easy way to think about this…

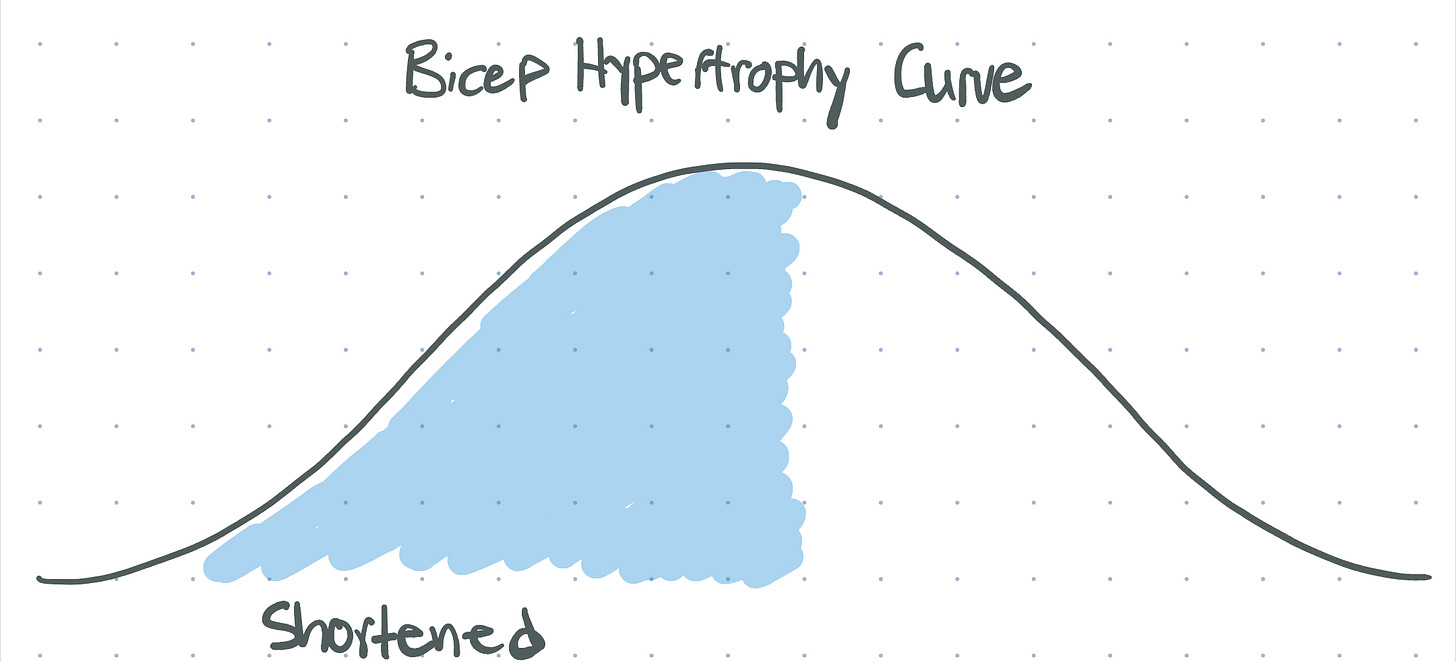

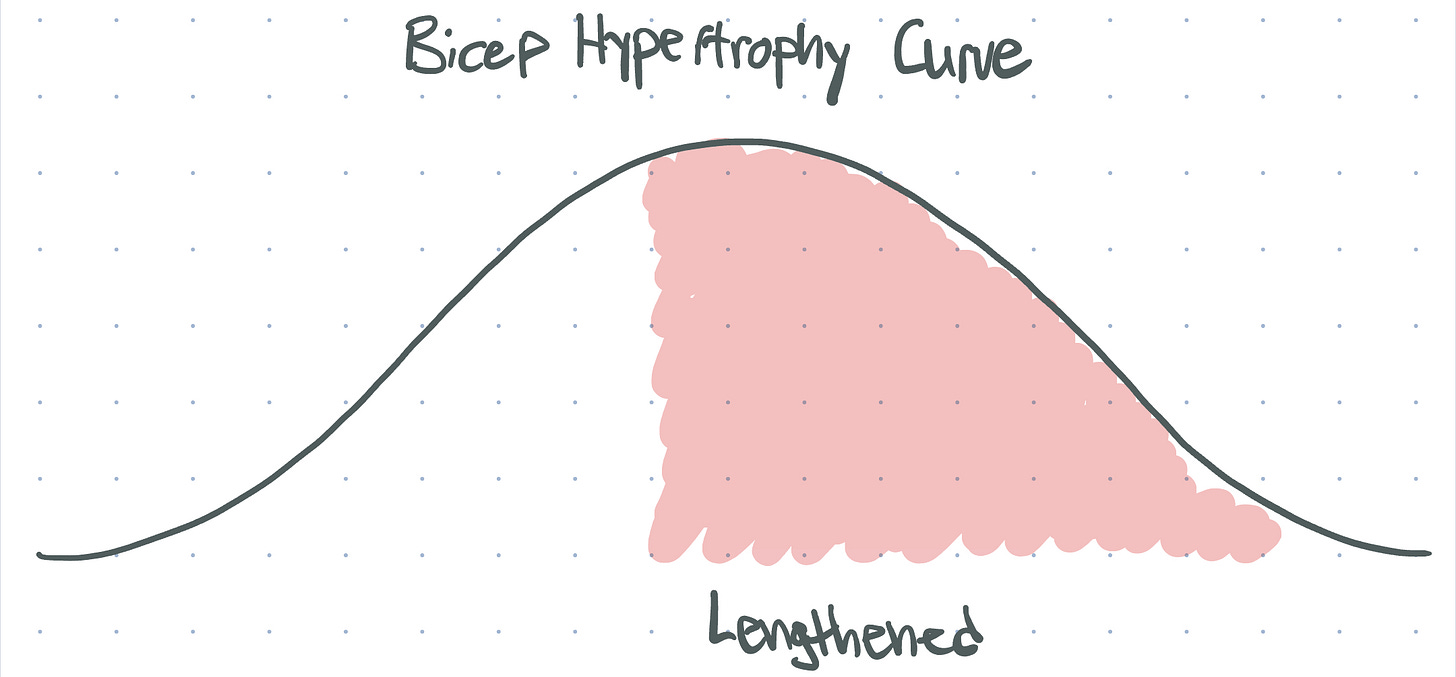

Imagine the bell curve below represents the training stimuli to make your biceps bigger:

In order to maximally stimulate your biceps and get them to grow bigger, you want to fill in the entire area under the curve.

If you train just in the shortened position, you’ll get a good stimulus but it won’t be complete:

And the same holds true for training just in the lengthened position:

Instead, you want to train both the shortened and lengthened position, which delivers a complete stimulus and fills in the curve:

5️⃣ Lift Tempo

Next up, let’s pivot to tempo training. Tempo refers to the pace of a lift or how long it takes to go through the eccentric (lengthening) and concentric (shortening) portion of a lift.

Let’s use a bench press as an example. Lowering the bar to your chest is the eccentric portion of the lift while pressing the bar up is the concentric portion of the lift. I can prescribe a 3-second eccentric, a 1-second pause on the chest, and an explosive concentric. Or I can prescribe a 3-second eccentric and 3-second concentric with no pausing or stopping.6 Or I can prescribe no tempo and tell the athlete to just go.

Importantly, each of these prescriptions can deliver a different outcome. Tempo is a powerful weapon for hypertrophy because you can manipulate metabolic stress and time under tension.

The slower the tempo, such as in the statodynamic method, the greater the metabolic stress gets. And it works via occlusion.

Constant muscle tension blocks arterial inflow and limits venous outflow. This means you limit 1) the delivery of fresh oxygen and nutrients and 2) the removal of metabolic byproducts like lactate, carbonic acid, and protons.

But remember, this is a balancing act. Hypertrophy is the love child of metabolic stress and mechanical tension, and you need both present to make magic happen. Slower tempos turn up metabolic stress, but also turn down mechanical tension.

This is the constant game you play. Everything operates on ranges and spectrums, and you should spend the majority of your time and effort on the fat part of the bell curve. Don’t get lost in the extremes. Just learn to utilize them in an effective way.

6️⃣ A Note on Pacing - Circuits vs. Supersets

In training, you will have the option to do exercises single file, as supersets, or together in a large circuit.

Here are some broad guidelines on how each of those methods provides a different stimulus:

Hypertrophy Training Guidelines

Tempo: slow and controlled eccentric (2-3 seconds on each rep) followed by a forceful concentric.

Hypertrophy Standards

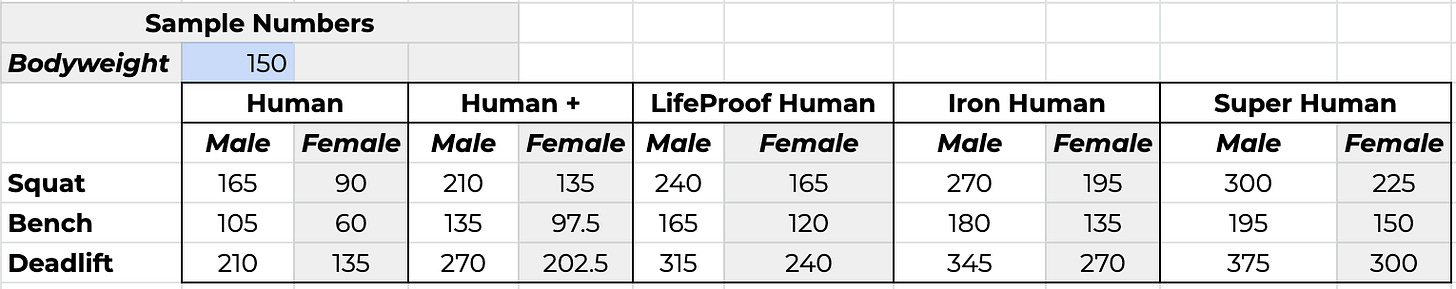

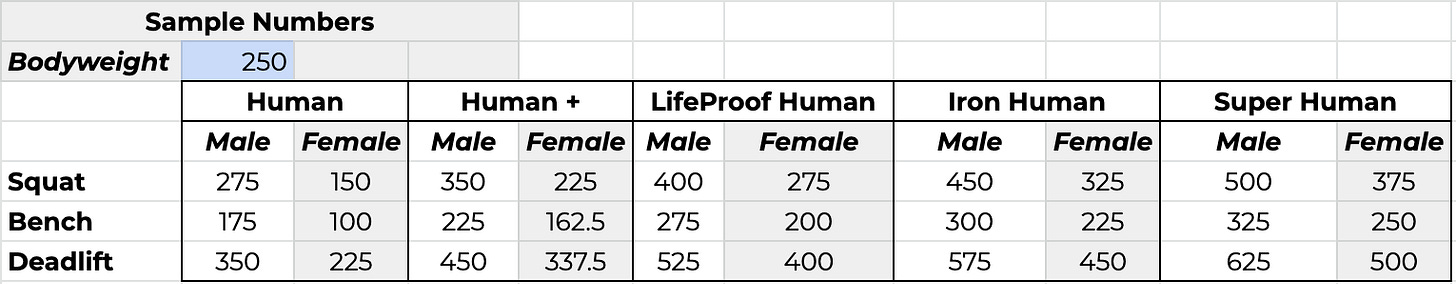

Here’s how our athlete classification system works (note: we have very high standards and you should too):

Level 1 = Human

Our baseline expectations for any functioning human

Level 2 = Human+

You laugh at mere mortals

Level 3 = Lifeproof Human

You are beginning to enter a league of your own

Level 4 = Iron Human

You are a savage

Level 5 = Super Human

You have evolved into a new species

Here are the numbers specific to hypertrophy. Obviously, hypertrophy is best measured by muscle dimensions, but we like to bias towards real-world performance, so we use a 12 rep max as our proxy of hypertrophy. It isn’t perfect but on average we’ve found athletes with a strong hypertrophy background (like bodybuilding) perform better at higher rep ranges.

Numbers are shown as a multiple of body weight. To calculate your standard, take your body weight and multiply it by the number in each cell.

Here are 3 examples of different body weights to give you real numbers to relate to (you can find the body weight in the blue box in the image).

In Closing

I’ll close with a quote from fellow Silverback coach Ryan L’Ecuyer:

“90% of success is having confidence. And 100% of confidence is having lats.”

I truly hope you found this foray into hypertrophy useful.

One of my hopes with this book is to simplify things so you can focus on application.

I think we often make things far more complicated than they need to be, and I’ve found that to be especially true in the realm of training and nutrition.

If you want to be the strongest in the world, win Mr. Olympia, finish first at the Tour de France, or be crowned the fittest person alive, then training and nutrition will be more complex because the outcome demands it.

But for the other 99.99% of the world that generally wants to look, feel and perform at their highest level, then I’ve given you (and will continue to give you) everything you need.

Finally - if you learned 1 thing from reading this, can I ask you to do me a favor and share it with just 1 friend or family member that will find it useful? It won’t take you longer than 10 seconds to share, and it’d truly mean the world to me.

Much love.

James

My projects (if you’re interested…)

🦍 The silverback training project – this is an exclusive 16-week training and nutrition coaching program for men that want to look better, feel better and perform better than ever before.

🤑 The wealthy fit pro – this is an exclusive 6-week coaching program for fitness professionals that want to get more clients and make an extra $1000-5000 per month online.

🏋️ Principles of strength and conditioning course – this is where I show you how to empower your own performance by teaching you to write training programs that get record results in record time for your physique, health, and performance.

💨 The oxygen course – this is a course for those brave souls that want to dive into the weeds and learn graduate-level respiratory, cardiovascular, and muscular physiology without the graduate school price tag.

Please note that this chapter does not get into enough depth if your goal is to step on stage and compete in bodybuilding. That’s a different game.

Think human with leg trapped under a boulder…the boulder has to be moved and then the human has to be carried.

If you refer back to the chapter on strength, you’ll remember that hypertrophy represents the peripheral component of strength.

Think rear delt isolation vs. lat isolation vs. full body squat

This should make logical sense in evolutionary terms. Carrying around excess muscle mass is crazy expensive in terms of the resources needed to sustain it. For that reason, the body doesn’t want to put on more muscle unless it 100% has to.

This is referred to as the statodynamic method